Introduction

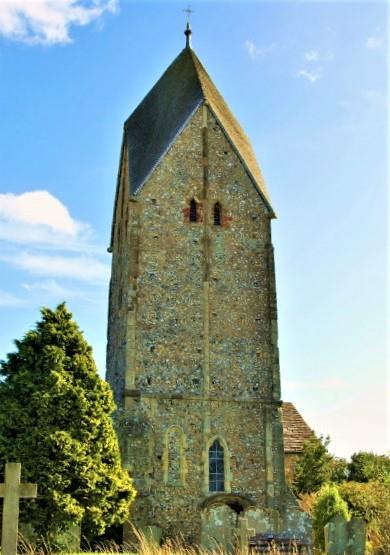

This article examines the first construction phase of the Old St. Helens church ruins (see Figure 1), to identify architectural features and uses the archaeology to determine the origin of the church fabric. Asking the question as to whether it was built by Anglo-Saxon or Norman craftsmen; before 1066 or after?

Figure 1 – Old St. Helens Church Ruins.

Figure 2 – Old St. Helens Church (Ore Church) from the North-West c. 1800 (From a drawing in the Sharpe Collection in Victoria History of the Counties of England – Sussex (Salzman 1937)).

Figure 2 is a scan copy of a drawing of how the church would have been seen in the landscape of

c. 1800 (Salzman 1937). The original medieval church underwent a series of additions and alterations right up until 1821. This church was replaced by the ‘modern’ St. Helens Church in 1869 (Salzman 1937, 88) which stands adjacent to The Ridge highway (B2093). Old St. Helens Church was no longer needed and was subjected to robbing and recycling of some of the building material. Exposure to the elements and ingress of vegetation plus vandalism in more recent times have reduced the church to ruins. It is now in the care of the Sussex Heritage Trust.

Figure 1 – Old St. Helens Church Ruins.

In 1987 recording work started on the standing masonry undertaken by Tim Morgan who carried out a stone-by-stone survey of the ruined walls; the north wall (north and south elevations of the nave and chancel), the east wall of the chancel (west and east elevations) and the west wall of the nave (east elevation). The remaining walls of the tower, all elevations interior and exterior were completed by Alan Dickinson in 1994 at a scale of 1:20. In 1994 the same year after Alan Dickinson completed his detailed stone by stone survey and while the scaffold was up on the church tower, Bernard Worssam, a geologist from Otford, Sevenoaks carried out a detailed stone recognition survey and produced a written report identifying the use of 9 different materials. All the stones were colour coded onto Tim Morgan and Alan Dickinson’s drawings as a separate set to go with Worssam’s report which has been referred to in this article. This was funded by Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group, Hastings Museum and Art Gallery and a grant from English Heritage.

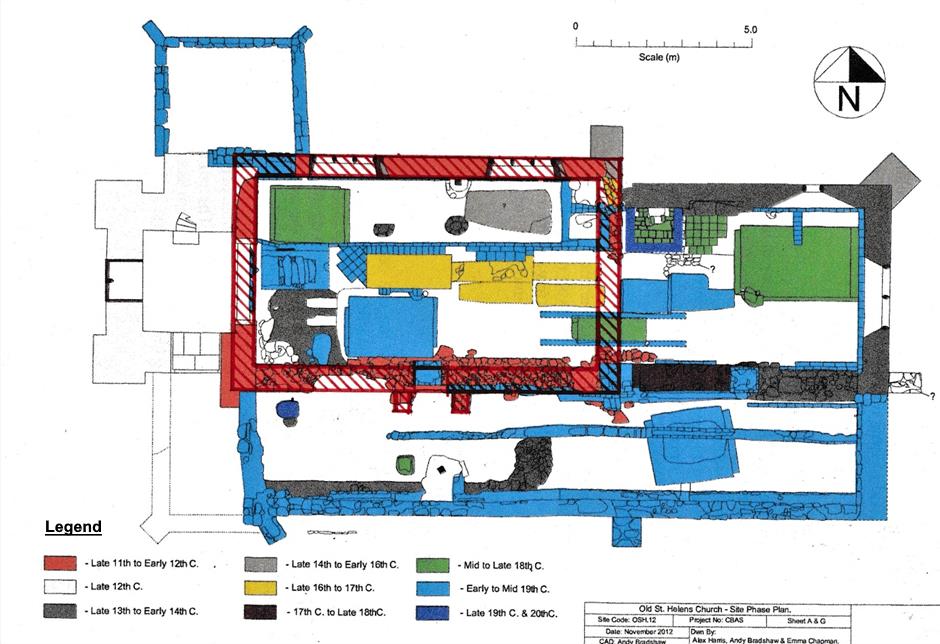

David and Barbara Martin, working for Archaeology South East, Institute of Archaeology, University of London, undertook an Archaeological Interpretative survey in 2012, in conjunction with an archaeological Investigation and Monitoring excavation by Chris Butler, Archaeological Services Ltd. for Sussex Heritage Trust the site owner, funded by a Heritage Lottery grant. The archaeological excavations were carried out by a community archaeological team under the direction of Mr A Bradshaw, Mr C Butler and Emma Chapman who produced drawings and a detailed report on the findings. The archaeological finds were deposited at the Hastings Museum and Art Gallery.

In the interpretative report Martin and Martin (2012) described Phase 1 (Late 11th or Early 12 Century) of the construction relying only on the evidence of the architectural features which they describe as Saxo-Norman in date. However, in their summing up of Phase 1 Martin and Martin (2012) report page 7 quote “In truth, apart from the window-head details of the north window, there are no extant features at Ore which support a Saxon origin for the present structure, no long-and-short work (description in Figures 3 and 5), no pilasters (as shown in Figure 8), no herringbone masonry (as shown in Figure 10) and no double-splayed windows. Even so it must be admitted that a late-Saxon date cannot be ruled out”. However, in the Archaeological Report by Chris Butler (2012, 122), Butler appears to be convinced that the church is a late Saxon date by the evidence of 11 sherds of late Saxon pottery, a silver penny of Harold I [1038-1040AD], all found in the nave of the Church. It can be projected that the pottery had been dropped by the Saxon builders and the silver penny lost by a parishioner or visitor to the church.

Figure 2 – Old St. Helens Church (Ore Church) from the North-West c. 1800 (From a drawing in the Sharpe Collection in Victoria History of the Counties of England – Sussex (Salzman 1937)).

The author of this article is looking at the Saxon architectural evidence of Old St. Helens Church in a new light, comparing it with other Anglo-Saxon churches in England and the counties of Sussex and Kent. Features in Old St. Helens church have been compared to other buildings and with details in publications by Warwick Rodwell (2012a; 2012b), Taylor and Taylor (2011) plus other renowned authors (see Bibliography at the end of this article).

There are many pieces of Caen stone used in the construction of the church tower, alterations to the west gable wall and north wall of the nave but no Caen stone is found in the original stonework of the nave walls. This appears to be good evidence that the Caen stones used in the church are later additions to the original stone fabric, c.1100. The North door must also have

been inserted at this time as it has Caen stone dressings. This dates the original nave stonework to be of the second half of the 11th century or later.

All photographs in this article have been taken by Paul Reed, author.

Location

Figure 3 – Location Plan with Old St. Helens Church indicated in red.

The church ruins and graveyard (Scheduled Ancient Monument No. 1011845 – NGR TQ 82047 12095, 135m AOD) are located off Ore Place Road, TN34 2LR about 500m south off The Ridge and 300m west of Elphinstone Road. The site has public open access and is well maintained, accessed by footpath from Ore Place Road and De Chardin Drive (see Figure 3).

Geological Evidence

In 1994, after Alan Dickinson had completed a detailed stone by stone survey and while the scaffold was still in situ on the church tower, Bernard Worssam geologist, completed a detailed stone recognition survey of all the standing masonry producing a written report which identifies 9 different materials, divided into three groups as follows:

Recent

Bricks and tiles

Bloomery Slag

Cretaceous (lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago)

Flint

Hastings Beds, sandstone undifferentiated

Hastings Beds, sandstone grey weathered

Hastings Beds, Ferruginous, silty

Purbeck Marble

Jurassic (lasted from about 201 to 145 million years ago)

Caen Stone (Limestone)

Oolite, undifferentiated (Limestone)

All the stones were colour coded onto Tim Morgan and Alan Dickinson’s drawings as a separate set to go with Worssam’s report which has been referred to in this article (Worssam 1994). Reduced sized drawings and reports are retained as part of the Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group archive. [To view, please contact the Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group Field Officers]. Copies of the drawings were presented to Sussex Archaeological Society and to English Heritage (now Historic England). The master drawings are held by Alan Dickinson along with rectified (ie. scalable) photographs by Ramsbury Photographic.

Historical Evidence

There is a detailed history of Old St. Helens Church written by F W B Bullock as a visitor’s guide leaflet from 1949 (Bullock 1949) and in 1951 Bullock published the book ‘A History of the Parish Church of St. Helens Ore, Sussex.’ (Bullock 1951). The author of this article managed to obtain a copy of the 1949 guide from Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group, chairperson Barbara Young.

Figure 3 – Location Plan with Old St. Helens Church indicated in red.

Due to the Covid-19 Pandemic with closure of the Hastings Reference Library the author was unable to have access to Bullock’s 1951 History of the Parish Church of St. Helens. However, the late David Padgham published a concise history of the church and adjoining manor in two Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group Journals (Padgham 2010, 5-11; 2012, 16-20). Padgham was always very meticulous in researching sources so readers can be assured that his articles are factual. Butler has also included an historical account as part of his archaeological report (Butler 2012, 8-11).

Padgham (2012 ,18) states that an ‘Ailric de Ore’ (a Saxon name) gave tithes to Battle Abbey

between 1107 and 1123AD. This did not necessarily mean that he was in possession of a manor but could have been a priest of this small church at Ore. Padgham writes in the same paragraph that this church could have been a mission church therefore unable to receive tithes. This would imply that this church was standing before 1107, and possibly prior to 1066. Padgham (2012, 18) also comments that the Caen stone used in the church could have come from Battle Abbey, left over from the finished abbey. Possibly, the Battle Abbey masons carried out the Caen stone work on St. Helens Church paid for by a benefactor living in Ore after 1100 or it could have been paid for by Battle Abbey. Padgham (2012, 18-19) states that there are no records that St. Helens was a mission church from a Minster or from Battle Abbey.

Evidence for the Architectural Detail

Long-and-Short stonework

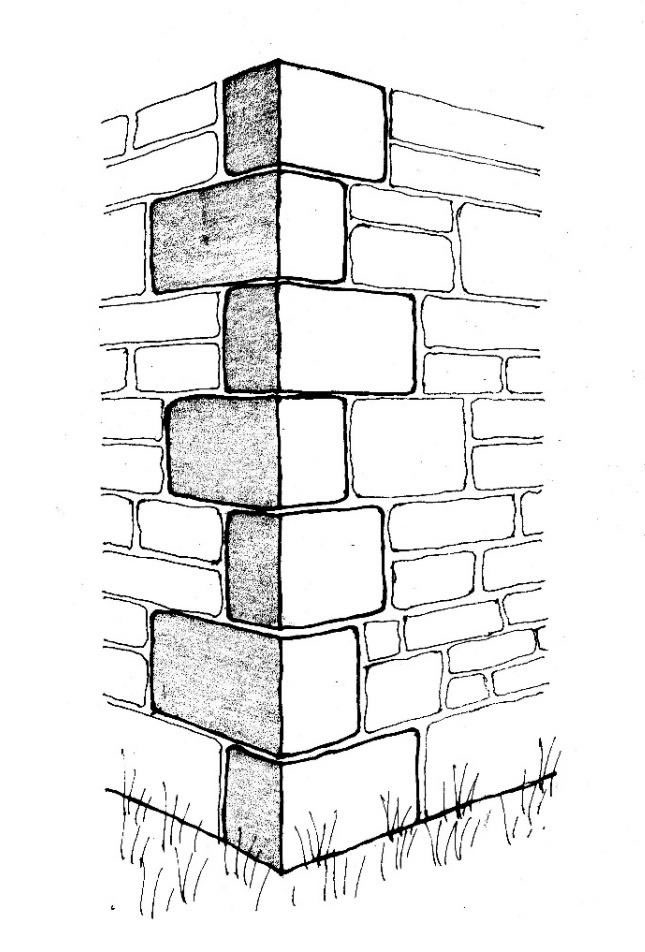

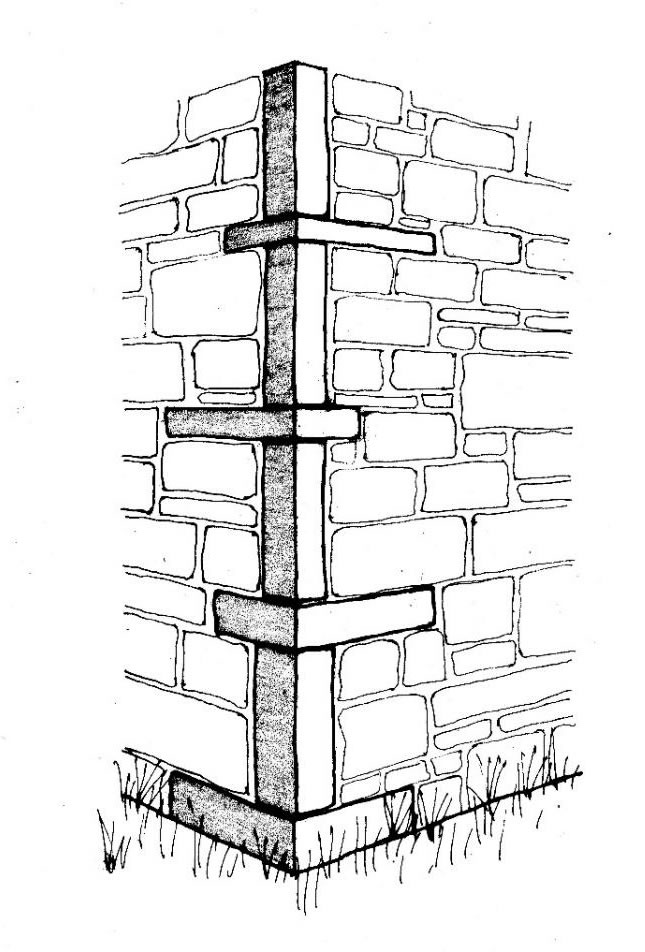

The external stone corners of a building are called quoins which go the full height of the of the building. Anglo-Saxon churches often have a distinctive pattern called long-and-short stonework where there is a long thin horizontal stone with a square or rectangular vertical stone bedded onto it usually about 600-700mm high but sometimes up to 1.5m high giving a very distinctive appearance (see Figures 4 and 6).

Figure 4 – Long-and-Short stonework on the South Porticus of St. Andrews Church, Bishopstone, East Sussex.

This arrangement of corner stones was common during the Anglo-Saxon period from the end of the 8th to the mid-11th century but did not continue after 1066. Bede wrote in The Age of Bede (2004, 191) that Benedict Biscop brought stone masons from Gaul France in 674, about 74 years after St. Augustine had built his stone abbey and churches in Canterbury. However, the long-and-short detail appears to be an English design and became commonly used south of the Humber Estuary. Not all Anglo-Saxon churches had long-and-short quoins, many churches just had rubble walling with no long-and-short features.

In Taylor and Taylor (2011, 944), Table 1 plus a distribution map (2011, 713 Figure 9), 68 examples of long-and-short stonework are listed. Examples in Sussex can be found at Worth, Poling, Sompting (see Figure 9), Bishopstone (see Figure 4) and Arlington. Taylor and Taylor’s Table 4 (2011, 950) gives 44 examples of rubble quoins with no long-and-short. Examples are found in Kent, at Lyminge, Lydd, Canterbury, Whitfield,Rochester and Reculver. This makes sense if there is no sound building stone to quarry in the area, only rubble stone or flints. Potter (2006) states that there are 12 Saxon quoin examples in Kent churches mostly on his list but these churches are not mentioned by the Taylor and Taylor (2011).

The stone used in Old St. Helens Church is the local Wealden Sandstone which may have come from the Fairlight Quarry and been transported on the ridgeway (The Ridge). Stone from this quarry was used in Rochester Castle in 1366 (Larking 1859, 112; Salzman 1923, 87). However, a local quarry (Sandrock Quarry) close by could have been used. Wealden Sandstone can be quarried in large blocks suitable for long-and-short work, but large blocks would be heavy to transport. If long-and-short or large alternative quoin blocks were used in Old St. Helens Church these blocks could have been robbed by the Phase 2 and 3 building work as the corner quoins have been covered by later masonry. The existing exposed corners of the Phase 1 part of the church do not survive so there is a possibility that this long-and-short feature or block quoins (see Figure 5) may have existed or it could have been built with rubble corners from the start

Figure 5 – Block quoin stonework as found in Roman, Saxon, Norman and later work. Drawn by Paul Reed.

Figure 6 – Anglo-Saxon quoins, known as ‘long-and-short’. Drawn

By Paul Reed.

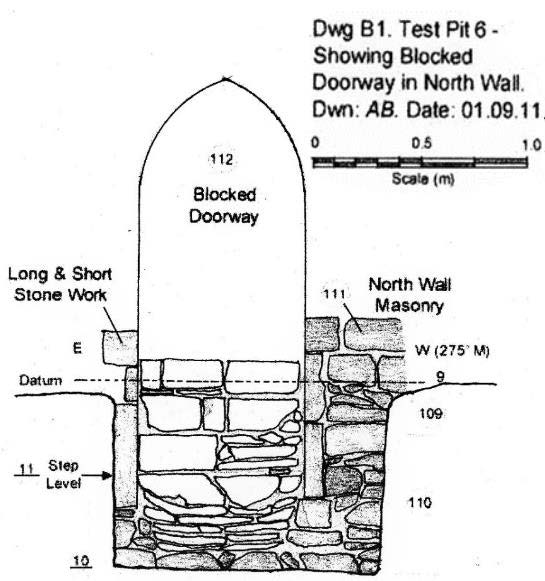

According to Martin and Martin (2012) the north door in the north wall of the nave was inserted in the 13th -16th century (see also North Door). However, Butler’s (2012, 71) report for Test Pit 6 describes the blocked door as having jambs of long-and-short stonework which is clearly shown in his drawing (Butler 2012, 73, Figure 21) (see Figure 8). The door opening which Butler believes to be Saxon in date not Norman and not 13th-16th century as claimed by Martin and Martin (2012). However, Worssam (1994) identified the jamb stones of this door to be of Caen stone (see Figure 10), not observed by Martin and Martin (2012), therefore the use of Caen stone is suggestive that the door was inserted c.1100 by Norman masons probably at the same time as the central window was inserted or made larger in the western elevation. From this we can confirm that the door jambs do not have original long-and-short Saxon detail as stated on Butler’s drawing (2012) (see Figure 8).

Pilasters

Pilasters in early stonework are the vertical columns of strip stonework found on the outer surfaces of exterior stone walling, usually built-in vertical dressed stone and made proud of the surrounding stonework, usually 150-200mm wide and protruding 50-75mm out of the structural face stonework

This feature when traversing the full height of the wall of the church or tower is known as strip-work. Between the pilasters the stonework was rendered (or made smooth using mortar) so that the strip-work stood out as an architectural feature. St. Peters Church at Barton-upon-Humber (Rodwell 2012a, 24-35) are good examples of strip-work and more locally at the St. Mary The Virgin Church, Sompting, West Sussex (see Figure 9).

The 9th century church at Bradford-on-Avon is a rare example being built with ashlar dressed stonework with relief strip pilaster decoration. Not all early churches have strip-work which is the case with Old St. Helens Church and along with many other early medieval churches in England. However, the Norman church at Kilpeck, Herefordshire, c.1140 has pronounced pilasters. Therefore, pilasters or strip-work cannot be used to date early churches.

Figure 7 – The blocked up North door (external view) of Old St. Helens Church.

Figure 8 – Chris Butler’s (2012) drawing of the North doorway in Old St. Helens Church showing ‘long-and-short’?

Figure 9 – The Church of St. Mary The Virgin in Sompting, West Sussex, showing pilaster stonework.

Figure 8 – Chris Butler’s (2012) drawing of the North doorway in Old St. Helens Church showing ‘long-and-short’?

Herring-bone stonework

Herring-bone stonework is found in Roman, Saxon and Norman masonry, sometimes it is used as decoration as in St. Peters Church at Diddlebury, Shropshire (Taylor and Taylor 2011, 213) where the Norman herring-bone work has been applied to the interior of the Saxon Church as a decorative feature. Taylor and Taylor (2011, 760), “that there is good evidence to show herring-bone fabric was used by Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Normans and later masons and therefore by itself it gives no indication for or against Anglo-Saxon workmanship”.

Often herring-bone work is done by the mason to quickly level up his work (see examples at Figure 11 and 12). As all churches were rendered internally and externally in most cases herring-bone work would not normally have been seen. Therefore herring-bone stone work cannot be used to date early buildings. There is a good example of 12th century herring-bone-stonework on the three elevations of the tower of All Saints Church, Beckley (see Figure 11 and 12), 8 miles north of Old St. Helens Church.

Figure 11 – Example of Norman herring-bone stonework on All Saints Church, Beckley, East Sussex.

Figure 8 – Chris Butler’s (2012) drawing of the North doorway in Old St. Helens Church showing ‘long-and-short’?

Single and Doubled Splayed Windows

Window in the north elevation

Most of the construction Phase 1 north elevation survives to eaves height. There is a surviving Phase 1 window above a blocked doorway on the north elevation. This window is of a typical Saxon/Norman style known as a megalithic single splayed window where the head of the window is made out of one piece of dressed stone. However, many early windows are made with rubble voussoirs and not using dressed stone. This design seems to rely on the materials the early stone mason had available at the time of making the window. There is an anomaly here as this type of window design continued into the 11th century so Martin and Martin (2012) could be right in their interpretation as it being of Saxo-Norman date. Double splayed windows are a characteristic of Anglo-Saxon stonework and were not often used by the Norman masons. Gloucester cathedral (1089-1100AD) is an exception, where the cathedral masons used double splayed windows in the eastern part of the Norman Nave. Brigstock Church Tower, Northampton, has single splayed lower windows, early Saxon work, and higher up the tower, has double splayed windows of late Saxon date (Taylor and Taylor 2011, 100-102, Figure 45). It is well documented that the Saxon and Norman stonemasons used both types of splayed windows.

Figure 13 – North wall single splayed window exterior view of Old St. Helens Church

Figure 14 – North wall single splayed window interior view of Old St. Helens Church.

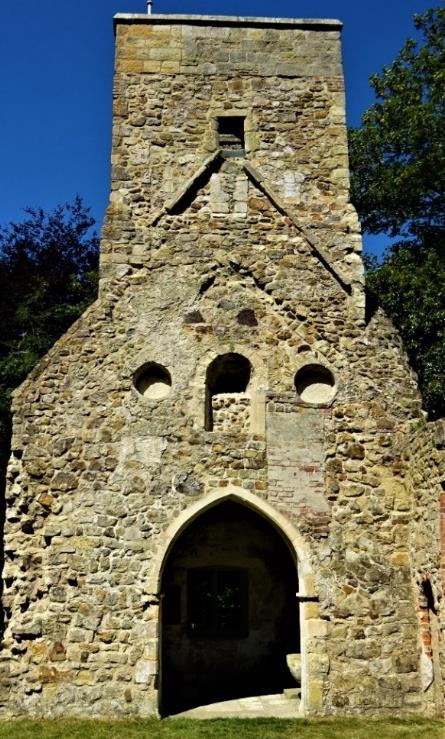

Windows in the west elevation

The west elevation is mostly of Phase 1 construction consisting of a central window high up in the gable with two round windows (oculi) either side which Martin and Martin (2012) comment is contemporary with a Norman date because the voussoirs and jambs are of Caen stone which can only be Norman c.1100 at the earliest (see Figure 16). There is no evidence that Saxon masons used stone imported from Caen. However, there is a possibility that there may have been an earlier opening which was replaced later in Caen stone as suggested by Martin and Martin (2012, 5) and Padgham (2012, 17). This Caen stonework around the window has a gritty mortar soffit. However, this would not explain that Martin and Martin (2012) had identified the same gritty mortar in the round oculi windows unless the round windows were remoulded at the same time as the insertion of the Caen stone in the centre window. The Norman stone masons could have used the same gritty mortar inside the round windows to match the mortar in the soffit of the new Norman central window, which is plausible, to tidy up all three windows while the scaffold was in place. In Martin and Martin (2012, 6) a gable photograph of the Norman church of St. Michael’s at Copford, Colchester, Essex which has a tall imposing central window with two oculi windows, one either side has been used as a comparison.

Round windows are found on many Anglo-Saxon and Norman churches usually high up, often in pairs and not always having a central window like at Old St. Helens Church and St. Michaels Church, Copford. Taylor and Taylor (2011, 853-4) mention circular windows in their study and they have recorded 54 circular Saxon windows including 21 churches having a total of 36 windows which are all doubled splayed including at Dover, Kent and Godalming, near Guildford, Surrey are listed in Table 9 (Taylor and Taylor 2011, 853-4). There is no comment as to whether the remaining 18 windows are of single splayed round design. Rodwell (2012b, 115) shows a Norman church (the Nave, West Barsham Church, Norfolk) with two oculi double splayed windows at a high level on a north wall with a door below having a semi-circular arch.

North Door

Can we assume, according to Martin and Martin (2012), that a 13th or even up to a 16th century benefactor wishing to fund new windows in the North wall of the church decided to remove the Norman semi-circular arch over this north door opening and put in a two-pointed arch over the existing opening re-using the existing springing points on the door jambs to make an impressive elevation of the north wall of the church (see Figures 7, 8 and 10). Worssam (1994) identified Oolite limestone voussoirs in the pointed arch above the springing stones including two Caen voussoirs possibly taken from the Norman circular arch above the springing line. Oolite limestone was used for the manufacture of the adjoining flat-headed windows either side of this door, very likely at the same time the door arch was changed. This would account for the disturbance of masonry below the small window above this door opening. This confirms that this door opening is very likely to be Norman work using Caen stone instead of the local stone which has been used in the construction of the north wall. This clearly confirms that this door was inserted later into the original north wall. The small megalith window is very likely to be original. The author of this article is in agreement with David and Barbara Martin that this door has been inserted later but not in the 13th -16th century. The door opening is also directly inline centrally under the small Saxon window above as if it was intended that they were architecturally linked to each other. The centre axis of the small window is also on the centre line of the front door on the south elevation (see Figure 21). Perhaps there might have been a narrow earlier door under this small window on the same central axis, replaced later to the present door opening. Opposite doors are very common on early buildings especially on earth-fast timber structures as seen on layout plans found on many archaeological excavations. This design is believed by many archaeologists and historians to be the origin of the cross passage found in later medieval stone and timber-framed buildings.

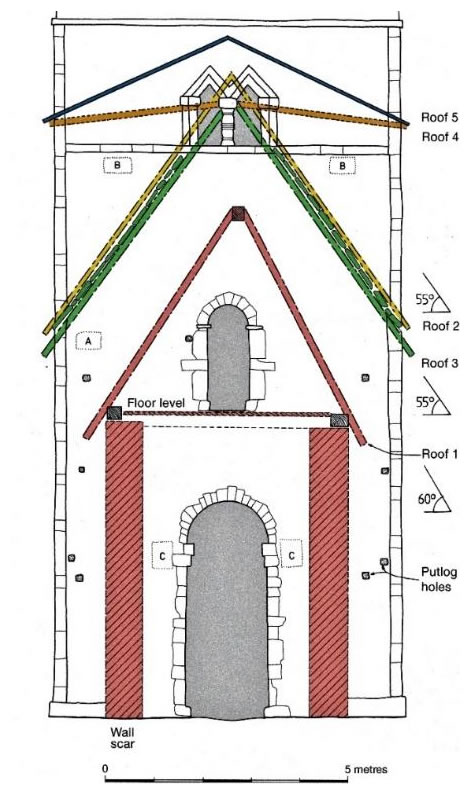

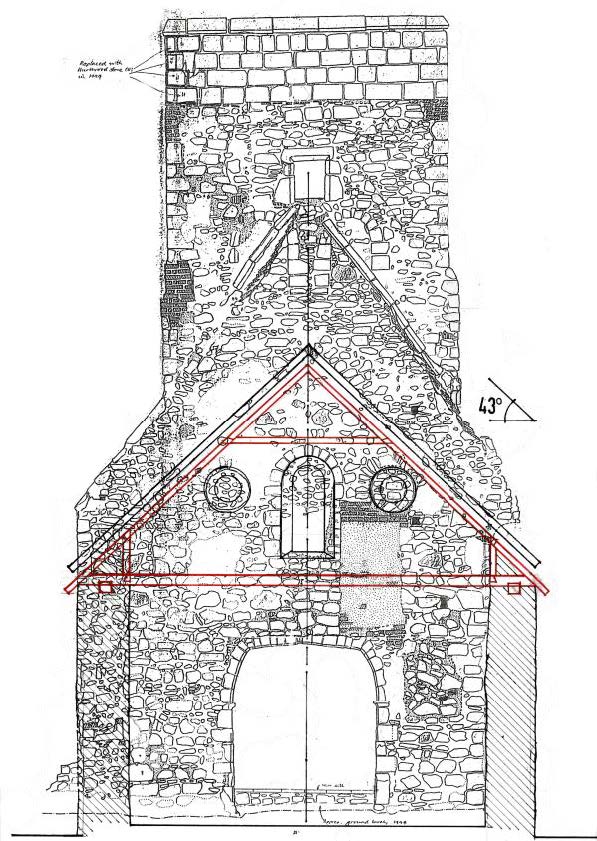

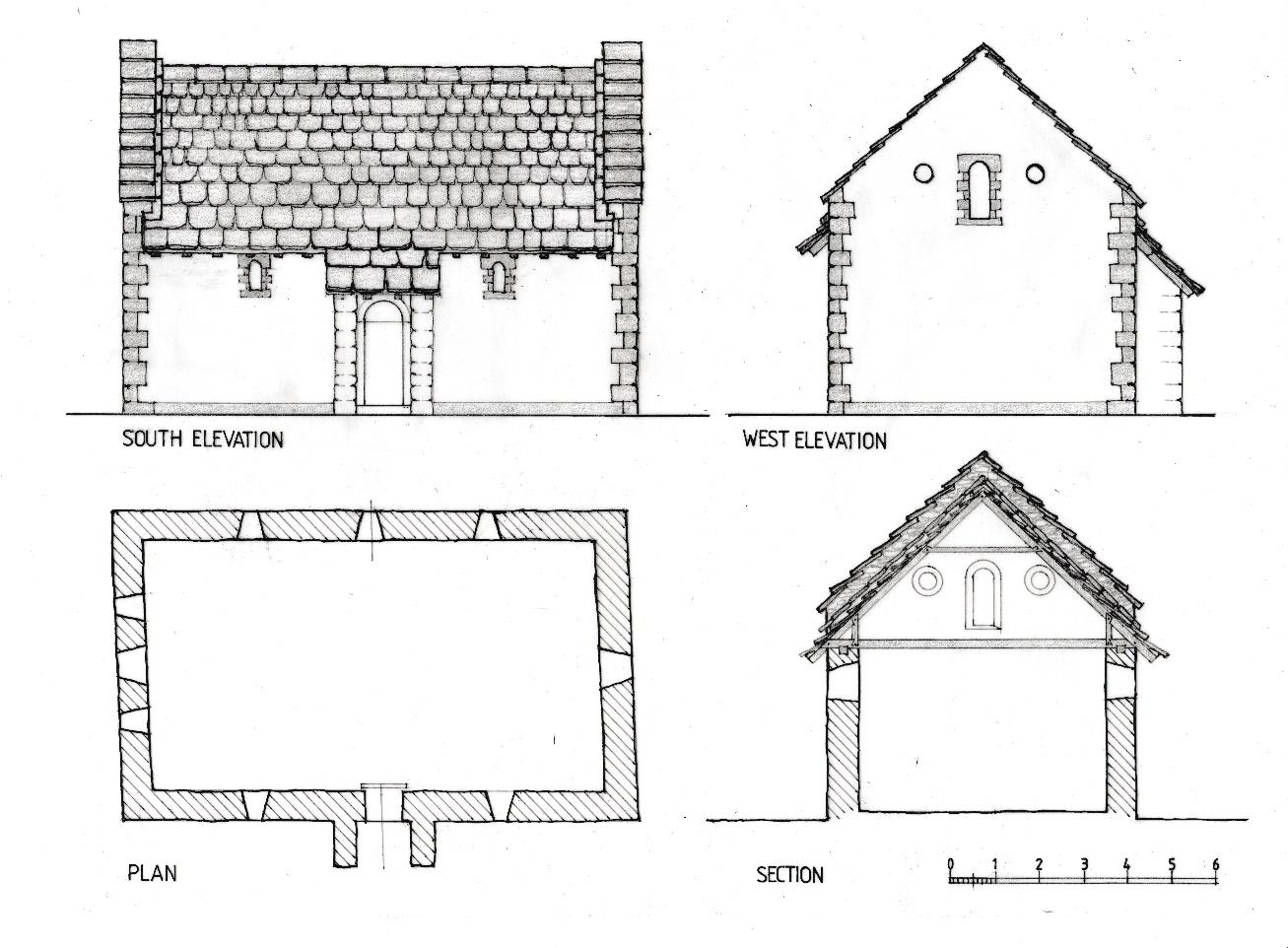

Phase One Roof

It has been established by Martin and Martin (2012) and by Butler (2012) that the complete west gable is part of the original structure of the early church. It consists of only three windows at high level: a central single light window with a semi-circular head flanked either side by round single splayed oculi windows set in rubble masonry (see Figures 16, 21 and the front cover of this journal). There could have been a central door at ground level which may have been removed when the arch opening was made into the tower in the 12th century. The ghosting of the roofline is clearly defined as seen from the interior of the nave (see Figure 16 and 17) having a roof pitch of 43o; however, Martin and Martin (2012, 5) report the roof pitch is 47o which is later changed to 45.2o with no explanation. Shallow roof pitches appear to be common in the Saxon period according to Taylor and Taylor (2011, 1060). A table of churches with known roof pitches of about 30-45o is given, however, the roof of the first Saxon church at St. Peters Barton-upon-Humber had a pitch of 60o, and a later pitch of 58o (see Figure 15). The author of this article has recently published an article in the Vernacular Architecture Journal titled ‘The Knowledge of Carpenters from the Early Medieval Period to the 18th Century in Setting out Roofs and Buildings without Geometry and Numerical Measurement’. This paper demonstrates how carpenters are able to set out roofs at angles of 43, 48, 52, 55, 58 and 60 degrees as found on Medieval and later buildings (Reed 2020, 30-49).

Figure 15 – East elevation of the tower at St. Peters Church, Barton-upon-Humber showing different Saxon roof pitches at 60 and 55 degrees. Drawn in 2011 by Warwick Rodwell (2012b, 283).

Roof covering

Recent correspondence with David and Barbara Martin has confirmed they had recorded the roof pitch incorrectly at 47o (Martin and Martin 2012, 5) when it should have been 45.2o. However, studying the recorded drawings by Morgan (1987) a pitch of 43o is shown for Old St. Helens Church (see Figure 16 and 17). This roof pitch is too shallow for thatch or shingles as these materials require a steeper pitch of 52o and above so that the rain water runs off quickly to prevent the material rotting prematurely.

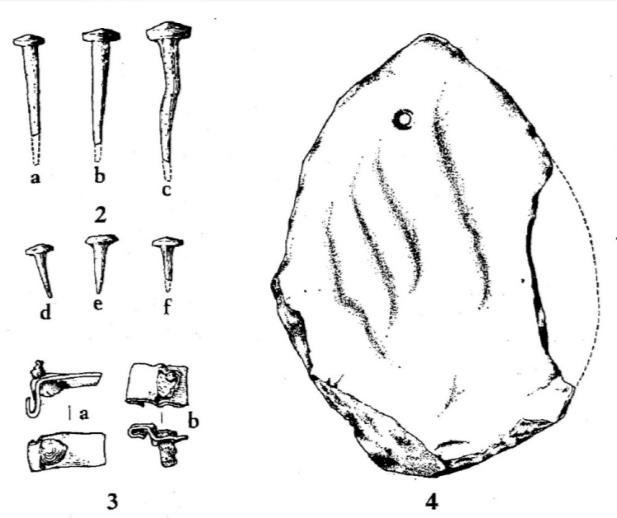

During the archaeological excavations in 2012, Butler (2012, 97) and his team found 47 pieces of Tilgate stone roofing slate identified as a local stone found in the Ashdown Beds (BGS 1980; Lake and Shephard-Thorn 1987). One piece of stone roofing slate had a hole in it for a peg or nail to secure it to a wooden lath. The finds from the 2012 excavations were deposited with Hastings Museum and Art Gallery. The museum staff were unable to retrieve the finds for viewing due to COVID-19 regulations and restrictions so the stone slate pieces could not be identified by the author of this article.

Figure 16 – Photograph of Old St. Helens Church showing ghosting of a Saxon roof pitch of 43o and a window in the west gable.

Correspondence with local Geologist Mr Ken Brookes (Chairman of the Hastings Geological Society) confirmed that Tilgate stone (known as Hastings Granit because it is very hard) could not be cleaved to make roofing slates. 43o is a suitable roof angle for slates but not clay peg tiles which require a pitch above 45o.

16th -18th century clay roofing tiles were found during the excavation on site (Butler 2012, 97-98) which were probably used on the later roof pitches of the church, but no medieval peg tiles were found.

Cramp conducted excavations at the Saxon monastic sites of Wearmouth and Jarrow on Tyneside (Cramp 1969, 21-66). She found limestone roofing slates with a hole for the slate to be fixed with a nail (see Figure 18). Additional to nails, fixings for sheet lead were also found at these two sites.

Lead sheet was used to cover the roof as a waterproofing measure would be more suitable for shallow roof pitches but no fragments of sheet roofing lead was found at Old St. Helens Church. Butler (2012, 88) in his archaeological report lists an assortment of iron nails. Item 11, 252 examples of square nails 60-70mm in length have been listed as coffin nails. These are more likely to be slate fixing nails.

Figure 17 – Morgan’s (1987) drawing of the west gable with the Saxon roof pitch highlighted in red by Paul Reed

Figure 18 – Stone slate 4, Slate nails 2, Fixings for lead-sheet 3 from Wearmouth and Jarrow (no scale given) (Cramp 1969).

The design of the Church Phase 1 & Phase 2

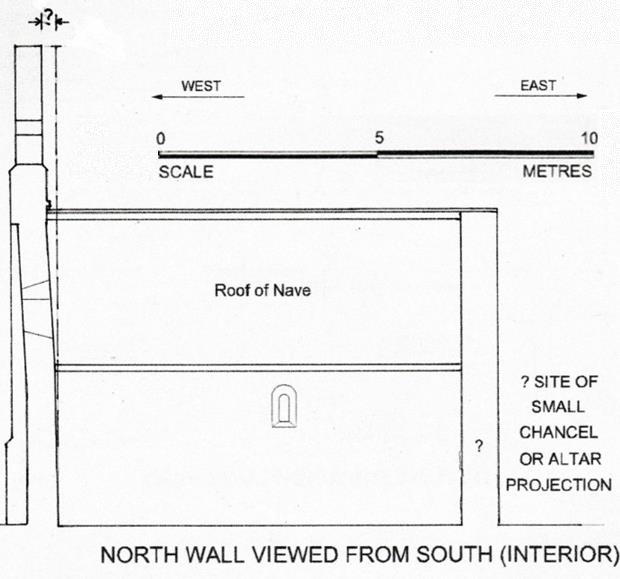

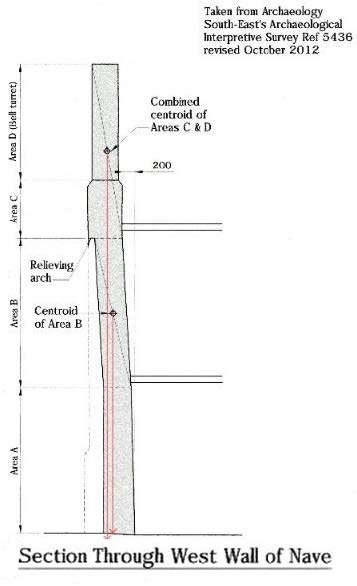

Phase 1 is described by Martin and Martin (2012, 28) as a blend of both phases as illustrated on drawing No.1751/6 being late 11th or early 12th century in date. Phase 1 consists only of a nave and there is no archaeological evidence for a Chancel. Phase 2, suggest Martin and Martin (2012) is the addition of the bell turret on top of the original west gable wall mainly built of Caen stone in about c.1150 with the tower being constructed 50 years later. The c.1150 date for the bell turret is based on the shallow pointed relieving arch made using Caen stone dressings that were added to the original Phase 1 west wall to thicken it, providing support for the bell turret. This shallow pointed arch can be seen from the first floor of the tower (Martin and Martin 2012, 29, Drawing 1751/7).

For a small church would been ideal to have a turret with bells to call a scattered congregation to Mass, probably one bell being sufficient. It would not have been necessary to build a tower next to the gable 50 years or less later. As part of Martin and Martin’s (2012) report there is a drawing of the section through the Phase 1/2 church labelled ‘the outline of the north wall viewed from the south (interior)’ (Drawing No. 1751/6). The section through the west gable wall and the bell turret shows the west gable wall to be leaning west by approximately 200m out of plumb [out of upright] (see Figure 19). Judging by Martin and Martin’s (2012) description of the bell turret it was very well-built using Caen stone ashlar dressings. Can we assume that a skilled stonemason built the turret on an already out of plumb original wall, hoping that by adding a relieving-arch the original west gable wall would be strong enough to support the bell turret?

Figure 19 – Martin and Martin’s (2012, 28) Drawing 1751/6, showing the west gable wall out of plumb.

The author’s observations on this anomaly are that the turret was built on top of the original rubble-built gable wall which had a lean to the west by about 200mm (out of plumb) which was reinforced and made thicker with the addition of a relieving arch made of dressed Caen stone to support it. It does not make sense that skilled Norman masons would build a bell turret on top of a leaning gable wall (see Figure 19). This anomaly was put to Roger Bunney, Consulting Civil and Structural Engineer (see appendix A) who confirms that this wall was strong enough to support the bell turret. Bunney (2020) suggests in his report that the bulge in the west gable wall was caused by the roof racking to the west. Medieval timber roofs were prone to lean over because they were only relying on the roof battens which secure the roof tiles or slates to keep the roof truss rafters upright and apart (see Figure 20). When the roof battens fail [decay] the lateral support for the roof also fails and the rafter trusses start to lean over slowly like a pack of cards and eventually lean onto the gable wall, possibly causing the wall to bow out as Bunney (2020) explains could be the cause in this case. The archaic roof of Kempley Church c.1120 in Gloucestershire, had masonry built up in between the truss rafters to prevent the roof from

racking, therefore if the Old St. Helens Church roof was built in the same way as Kempley (Morley 1985), roof racking may not have caused the weakness in the west gable wall causing it to lean. According to Martin and Martin (2012) a tower was built up against this gable wall and bell turret added approximately 50 years after the turret was first built. The tower has strengthened the west gable and in doing so has preserved it to this present day. The Chancel was added to the church a hundred years after the tower had been built. There may have been a need for this small church to have a very large tower, maybe to act as a land mark?

Figure 20 – Conjectural plan and elevations of the Phase 1 Saxon Church of St. Helens before 1066. Drawn by Paul Reed.

Discussion

There has been much speculation about the date of the original church, however, with a review of the evidence in this article the author is in agreement with Padgham (2010; 2012) and Butler (2012) that the church was built before the bell turret, when the north door was added. The main evidence for this is the following facts:

1. The original builders had left broken drinking and food storage pots (Saxon pottery) on the building site with the shards only being found in the nave area which is the oldest part of the church.

2. When the church was in use a Saxon silver penny (King Harold I struck 1038-1040AD) was dropped and lost in the nave, however, there is a small possibility that this coin could have been dropped after 1066.

3. The small single splayed window above the north door is of an early design having a megalith window head. Taylor and Taylor (2011) have observed on many early churches that some of the windows are single splayed and do not always have double splayed reveals. This is the case for the two round oculi windows in the west elevation of Old St. Helens Church.

4. The central window in the original west elevation has been enlarged using Caen stone, very likely when the bell turret was built also using Caen stone, which makes this work later than the original early building.

5. If the Norman builders built the original nave in c 1100, they would have used Caen stone dressings for the small window above the north door and this is not the case.

The north door was inserted about 50-100 years later and had jambs made with Caen stone dressings, the same as the central west window however, Caen stone was not used on the circular windows.

Figure 21 – Phase 1 Church plan hatched in red by Paul Reed on Chris Butler’s (2012, 123) archaeological plan.

According to Martin and Martin (2012) the ‘Jury’ is still out on the grounds that the assumption is that the Normans built the nave in c.1100 and not having access to Caen stone, used the local stone as there was good source. If David and Barbara Martin are right, then it is possible that the nave was built by Saxon/Norman masons under the direction of a Norman benefactor after 1066.

Not having access to Caen stone until later when the central window was inserted, the bell turret was built on top of the west gable, hence being called Saxo-Norman. After the Battle of Hastings in 1066 there was probably much unrest in the Rape of Hastings and it must have taken quite some time for building work to resume again, not until c.1100 at the earliest. Martin and Martin (2012) did not mention the Caen stone used on the inserted north door which was identified by Worssam (1994) making it very likely to be Norman and not later.

However, there could have been an earlier north door which would have lined up with the south door being central in the building. Central inline doors are common in very early medieval buildings and it is believed that this is the origin of the medieval cross-passage that is found in the houses of the mid and late medieval period.

The author of this article is saying the ‘Jury is in’; Phase 1 was not Norman built in c.1100, but in his interpretation based on Padgham (2010; 2012) and Butler (2012) historical research on the church plus discussion points 1-5 listed above, the author’s view is that the church was built before 1066, sometime between 950-1050 as a simple one cell church (see Figure 20 and 21). This view is also supported by Butler (2012, 122) in his archaeological report.

The author has drawn a conjectural elevation and section of this phase (see Figure 20) and a perspective view illustration which is on the front cover of this journal. The church is illustrated as having three windows on the west elevation, one on the north elevation but there could have been a total of three. Also, a single window above the alter on the east elevation and two on the south elevation with a central entrance door and porch.

There is evidence of porch foundations midway along the south wall according to Butler’s (2012, 123) archaeological phased plan (see Figure 21) with a window either side of the entrance (see Figure 20). Phase 1 was built by Anglo-Saxon builders between 950 and 1050. Phase 2 is c.1100 when the Norman masons added or replaced the north door, enlarged or replaced the central window on the west elevation and built the bell turret as a single-phase using Caen stone, maybe funded by Battle Abbey or a new lord of the manor.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Kevin and Lynn Cornwell for editing this article and supplying copies of Bernard Worssam’s and David Padgham’s reports; to Alan Dickinson for printing off a copy of his and Tim Morgan’s stone-by-stone drawings and his report, colouring up a copy set of drawings by Bernard Worssam giving the geology of the building stones of the church and a copy of Bernard’s report; to David and Barbara Martin for a copy of their report and all the site photos and for their constructive comments. Thanks to Andrew Ward, Assistant Historic Environment Records Officer, County Archaeology Department, East Sussex County Council for providing the Chris Butler archaeological reports. Anne Scott at The History House, Court House Street Hastings and Barbara Young, Key Keeper of Old St. Helens Church Tower and Chairperson of Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group, for a copy of a visitor’s guide to Old St. Helens Ruins by F.W.B. Bullock. Philip Hadland of Hastings Museum and Art Gallery for looking for the site finds but was unable to retrieve them because of COVID-19 restrictions. For Christine Reed assisting me with the site levels and measurements. Ken Brooks local geologist, Chairman of the Hastings Geology Society for his advice and discussion on Tilgate stone. Roger Bunney Consulting Civil and Structural Engineer for his comments regarding the structural stability of the bell turret and providing a report and drawing seen at Appendix A; Chris Butler for a copy of his drawing on page 73 of his report. David and Barbara Martin, plus Warwick Rodwell for his drawing seen at Figure 13.

Appendix A

Structural drawing and observations on the west gable wall of Old St. Helens Church by Roger Bunney (2020).

1. Assuming that the drawings within David and Barbara Martin’s report are reasonably accurate, I have imported their section through the west wall into AutoCAD and scaled it up using their scale bar. I’ve attached a copy, which I have marked up into areas for ease of reference against my comments below.

2. You have referred to the west wall as being 400m out of plumb but I can’t see where you’ve got that figure from. From the dimensions that you have shown on your sketch? It looks as though you have included the Caen stone offset at the base of the turret within your measurement which should be deducted and, in any event, the actual dimension from CAD is only of the order of 200mm.

3. The wall is not shown with a consistent lean and it is noticed that the outside face of Area A is within reasonable limits of plumb, which of course would originally have been restrained by the north and south walls at its corners.

4. The obvious lean is to the Area B gable triangle and I would suggest that racking of the roof was the most likely cause of its original displacement, rather than overall outward rotation of the wall due to some form of subsoil failure.

5. Your theory that adding the additional weight of the bell tower caused it to become ‘live’ doesn’t really hold true because for the wall to begin to become unstable, its centre of gravity would need to fall outside the width of its base and even if you ignore the added benefit of the relieving arch, neither the centroid of the leaning Area B, nor the combined centroid of Areas C & D fall outside the base thickness of the wall.

6. Notwithstanding the above, I would suggest that it is highly unlikely that even if the wall was actively moving to such an extent that propping against the relieving arch had caused it to deform from a semi-circular to a pointed arch, this would have been such a dangerous situation that surely, they were more likely to have considered rebuilding the wall, rather than leaving it timber propped for the time it took to build the tower as a buttress?

7. The photograph of the relieving arch D25 at Appendix A (p24) within David and Barbara’s report, along with its description, shows neatly dressed Caen stone voussoirs, all evenly joined and I couldn’t see any evidence to suggest that it had become displaced by accidental loading. Also, I would suggest that the very nominal bonding of the straight joint D43 between the tower and the west wall shown at Appendix A (p. 26 & 27) is not consistent with the intention for the tower to act as a buttress.

References:

Bede, Venerable 2004. Edited and Translated by Farmer, D.H. The Age of Bede, London: Penguin Classics.

British Geological Survey 1980. Hastings and Dungeness Sheet 320/321, Solid and Drift Edition, 1:50,000. Southampton: Director General of the Ordnance Survey.

Bunney, R. 2020. Structural drawing and observations on the west gable wall of Old St. Helens Church. Unpublished.

Butler, C. 2012. An Archaeological Investigation and Monitoring at Old St. Helens Church, Ore, East Sussex. Berwick: Chris Butler Archaeological Services. Unpublished

Bullock, F.W.B. 1949. Ruins of The Old Parish Church of St. Helen. Ore. Sussex. A Short Guide for Visitors. Publisher unknown.

Cramp, R. 1969. Excavations at the Saxon Monastic Sites of Wearmouth and Jarrow, County Durham: An Interim Report. In: Medieval Archaeology Vol. 13, 21-66.

Lake, R. D. & E. R. Shephard-Thorn 1987. Geology of the country around Hastings and Dungeness – Memoir for 1:50,000 geological sheets 320 and 321 (England and Wales). London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Larking, L. B. 1859. Fabric Roll of Rochester Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 2, 112. Kent Archaeological Society.

Martin, D. & B. Martin 2012. An Archaeological Interpretative Survey of Old St. Helens Church, Ore, East Sussex. Project Ref. 5436. Archaeology South-East Institute of Archaeology University College London.

Morgan, T. 1987. Report on Old St. Helens, Ore. Unpublished.

Morley, B. M. 1985. The Nave Roof of The Church of St. Mary, Kempley, Gloucestershire. In: The Antiquaries Journal, No. 65, 101-111. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Padgham, D. 2010. The Origins of Ore – a new look at the evidence. In: Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group Journal New Series No. 30, 5-11.

Padgham, D. 2012. Old St. Helens Church Ore – A summary of previous activities and an overview of major new report on the architecture by D&B Martin. In: Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group Journal No. 32, 16-20.

Potter, J.F. 2006. Anglo-Saxon building techniques: quoins of twelve Kentish Churches reviewed. In: Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 126, 185-218. Kent Archaeological Society.

Reed, P. 2020. The Knowledge of Carpenters from the Early Medieval Period to the 18th Century in Setting out Roofs and Buildings without Geometry and Numerical Measurement. In: Vernacular Architecture Journal Vol. 51, 30-49. Abingdon: Routledge Taylor and Francis.

Rodwell, W. 2012a. Appearances can be Deceptive: Building and Decorating Anglo-Saxon Churches. In: Journal British Archaeological Association vol. 165, 22-60.

Rodwell, W. 2012b. Archaeology of Churches. Stroud: Amberley Publishing.

Salzman, L.F. 1923. English Industries of the Middle Ages, 87, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Salzman. L. F. 1937. The Victoria History of the Counties of England – Sussex. Vol. 9, The Rape of Hastings. University of London Institute of Historical Research. London: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, H.M. & Taylor, J. 2011. Anglo-Saxon Architecture Vol.1-3, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Worssam, B.C. 1994. Report on the Building stones of Old St. Helens Church, Ore. Unpublished.

Bibliography:

Bullock, F.W.B. 1951. History of the Parish Church of St. Helen. St. Leonards-on Sea: Budd and Gillatt.

Butler, C. 2010. An Archaeological Topographic and Ground Survey of Old St. Helens Church, Ore, East Sussex. Berwick: Chris Butler Archaeological Services. Unpublished.

Lott, G. & D. Cameron 2005. The Building Stones of South East England: Mineralogy and Provenance. British Geological Survey.

This research is still ongoing...

Please check this website regularly for updates on new articles on how master craftsmen built medieval buildings - Isn't it interesting to know how long is a piece of string!

Get in Touch

Please get in touch using our contact form or by phone.

Mobile: 07711545618